NYFF61 Review: Poor Things

Yorgos Lanthimos and Emma Stone reach new heights in this sex-positive fairy tale

Fresh off its Golden Bear win in Venice, Poor Things, iconoclast director Yorgos Lanthimos’ newest, screened to a full house of eager festival goers in Alice Tully Hall. If the sudden excited buzz surrounding Lanthimos’ horny gothic fairy tale indicates anything, it’s that the film might be his most accessible yet. Ironic, considering the sheer amount of fucking Emma Stone’s baby-brained-Frankensteiness Bella Baxter does, and the current moment in which the conversation surrounding the general depiction of sex on-screen leans increasingly prudish.

Lanthimos, whose acclaimed black comedies seldom avoid confronting sex, seemed well aware of the ongoing debate when asked to comment at the Q&A, maintaining that “we felt that we shouldn't shy away from it…it would feel very disingenuous.” It’s a film that—through Bella’s rapid and delightfully written development from a petulant woman-child to a fully-embodied, sexually empowered person—treats all the taboos and rituals, from religion to marriage to sex work, as fair game in its hilarious deconstruction of how one is socialized. Lanthimos and writer Tony McNamara (The Favourite) embrace Bella’s sexual awakening and treat it as the fulcrum of her entire self-actualization, indulging its many absurdities and laying bare questions of consent, bodily autonomy, and sexual desire.

Bella Baxter is a woman without inhibition. The product of her mad scientist guardian Godwin Baxter’s (Willem Dafoe, striking a magical chord of rompy sincerity) outrageous experiment, in which he transplants the brain of a suicide victim’s unborn child into the deceased mother’s head, she starts as an infant in a grown-woman’s body, speaking gibberish and throwing glass-shattering temper tantrums. “What a pretty retard,” Ramy Youssef’s Max McCandles, Godwin’s bright-eyed lab assistant remarks in the film’s opening minutes—except her condition is not a handicap, but rather a blank slate psyche with all the bodily faculties of an adult woman, ripe for precipitate maturation.

It’s a transformation that hinges on over-the-top performance that runs the gamut of human emotion—the type of thing that risks sinking a film in the hands of the wrong performer. Of course, in what might be her most arresting performance, Emma Stone brings Bella Baxter to life with a dynamic blend of slapstick physicality, audacious verve, and potent sensuality. Stone’s linguistic dexterity alone is something to behold—with each new experience, Bella’s command of grammar and vocabulary improve seamlessly.

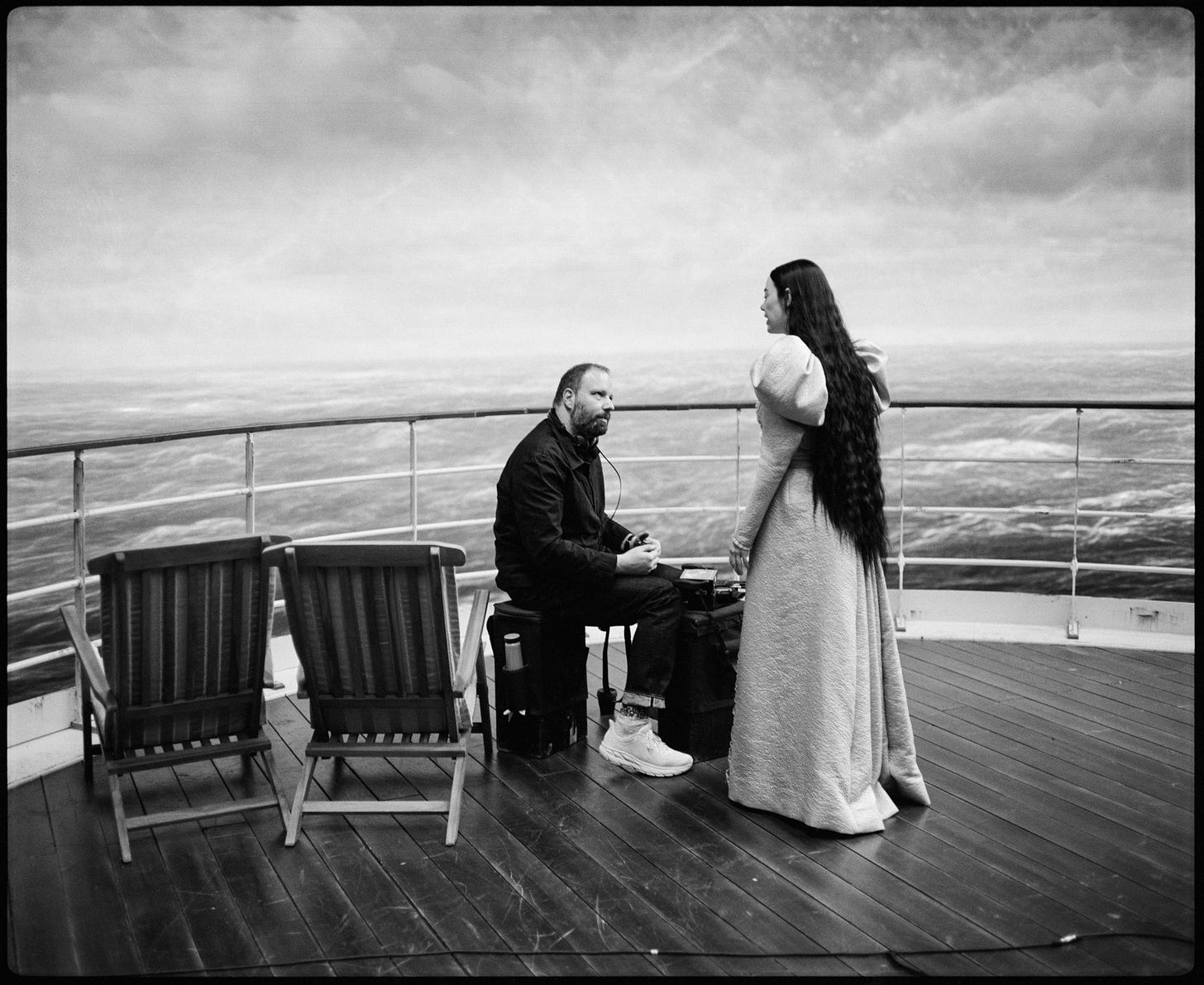

As evidenced by her acclaimed turn in Lanthimos’ 2018 film The Favourite, Stone’s capacity for idiosyncratic performance pairs well with Lanthimos’ off-beat style and dry sense of humor. Here, the vulnerability required for the role suggests that the pair have also built a solid foundation of trust. “There’s no world where I would have done this project with anybody else. I think you could probably feel it when you watch the film that I trust Yorgos implicitly,” Emma Stone told Vogue Magazine. Indeed, that trust is just as palpable as the sense that these two are at the height of their collaborative powers (Stone additionally starred in Lanthimos’ short film Bleat, which also premiered at the festival). Step aside, Colin Farrell, there's a new muse in town.

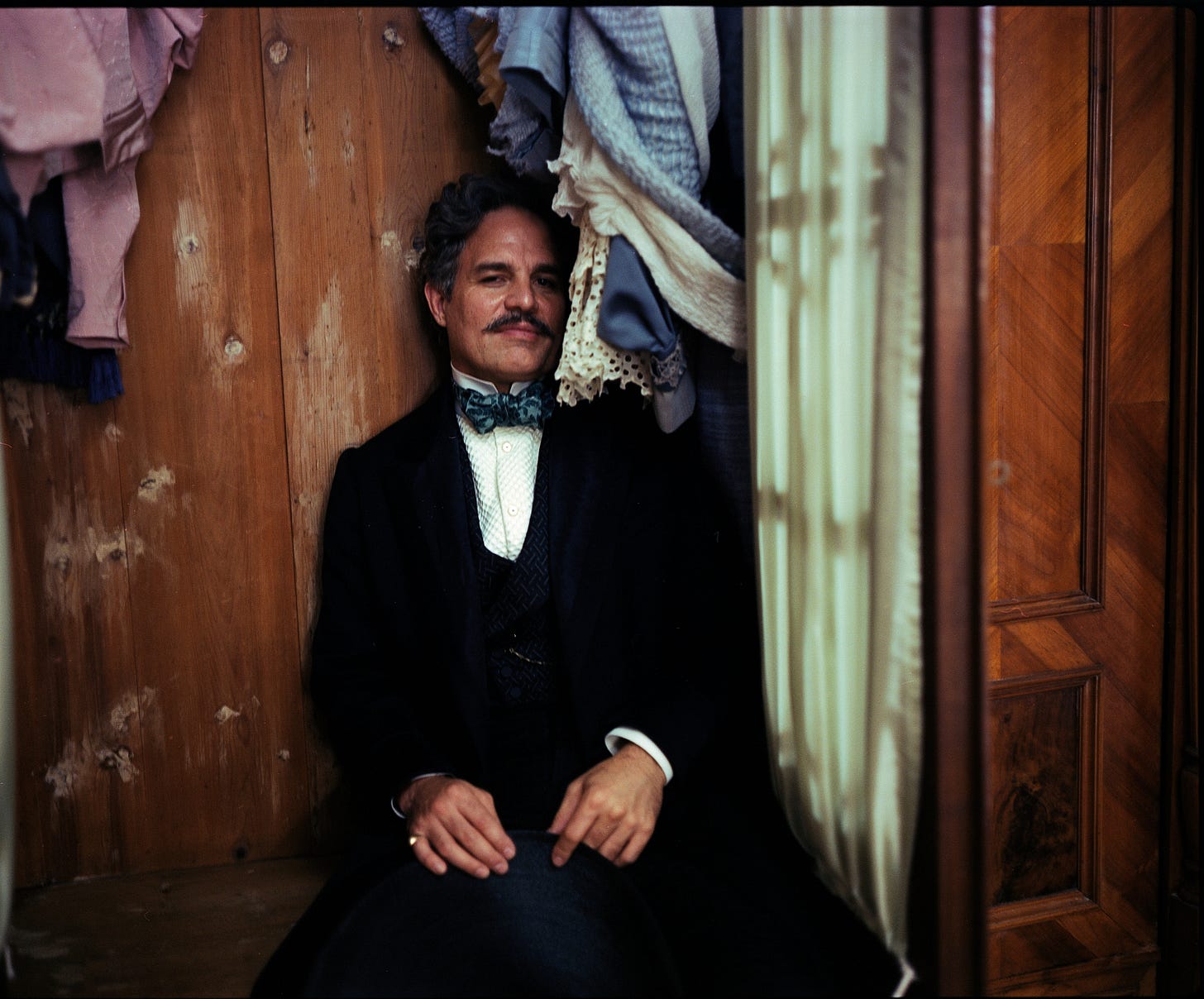

The film also boasts a splendid menagerie of first-time Lanthimos collaborators: Defoe and Youssef as Bella’s peculiar father-figure and earnest first (of many) suitor(s), respectively; Mark Ruffalo as a drunken sleazeball hellbent on coveting Bella; Christopher Abbot as a foreboding stranger from Bella’s past life; Kathryn Hunter as a motherly brothel madam; Margaret Qualley in a small but riotous supporting role as a newer subject of Dr. Baxter’s; and the unexpected combo of Jerrod Carmichael and Hanna Schygulla (!) as a pair of bookish luxury cruisers.

By now, audiences might come to expect singular characters from Lanthimos’ high-concept films—and the eccentric, at times professionally anomalous, performances from the A-list talent who embody them. Thus, Lanthimos’ recent filmography might be described as dwelling in the brackish water where the mainstream meets the arthouse. Here, save for a handful of moments in which a performer briefly slips out of the elusive pocket between deadpan and suggestive, the ensemble elevates the film to an entirely different level. These are characters and performances that feel truly iconic—Bella exclaiming ”Bella discover happy whenever she want!” after fulfilling her masturbatory urges with an apple is just one of many memorable one-liners—and which lead me to believe that the film might have a degree of staying power hitherto unrealized in Lanthimos’ work.

It is this element of rewatchability (I will undoubtedly catch the film again upon its wide release) that separates Poor Things from the rest of Lanthimos’ filmography for me. As much as I relish the cruel absurdity and stylistic finesse of films like The Lobster or The Killing of a Sacred Deer, Lanthimos’ English-language entries can still be quite austere. Even The Favourite, with all its skillful melodrama and latent playfulness, has a biting coldness to it. This is not to say Lanthimos lost his transgressive edge with Poor Things—quite the opposite: it’s here, only this time on an operatic scale. Instead of holding you at a distance, the film sweeps you up in its resplendent world.

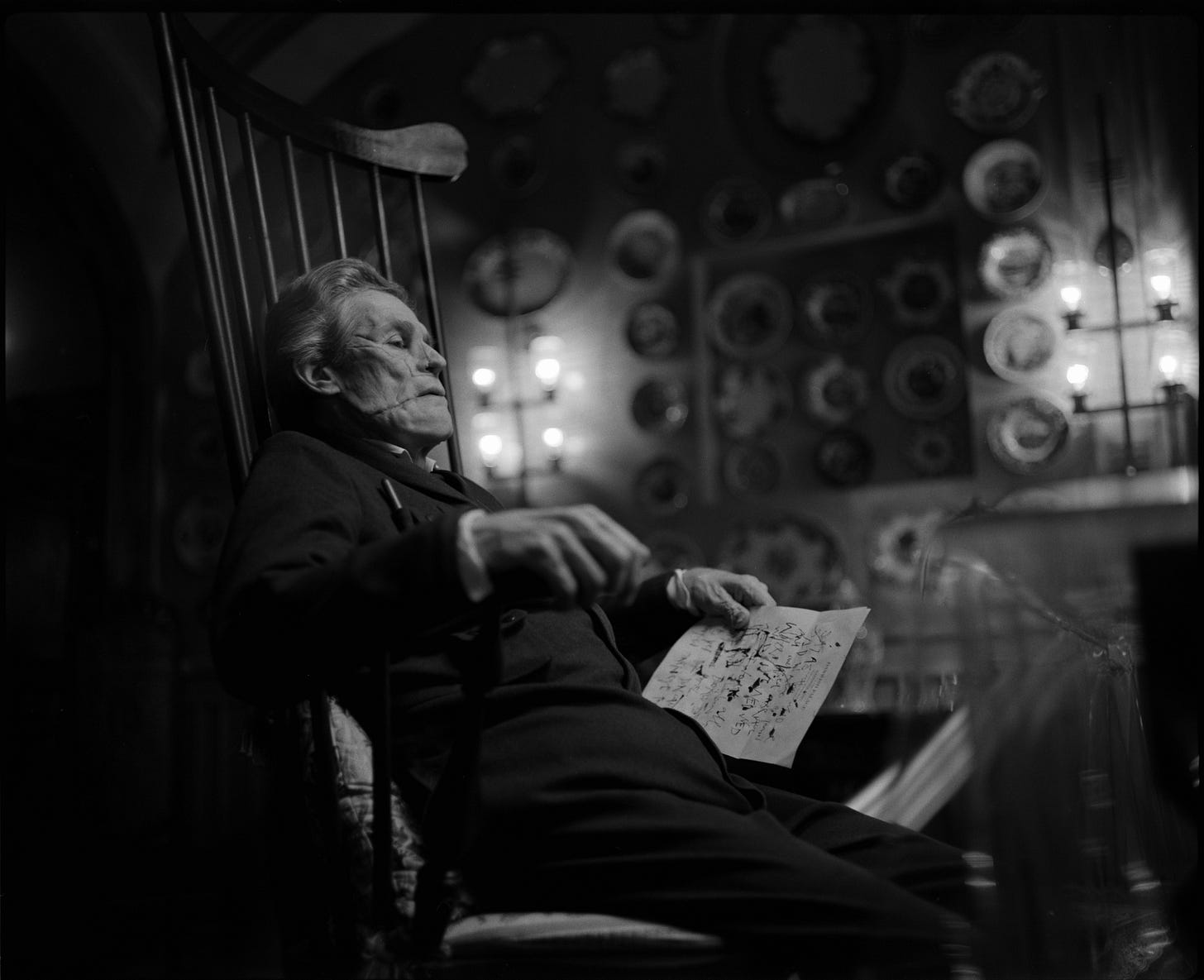

Enormous credit is due to the film’s production and costume design, which eschews period and plays with it at the same time. Costume designer Holly Waddington’s outfits evoke a sort of Victorian futurism, like The Favourite on psychedelics. It’s a singular aesthetic that suits the film’s whimsical characters beautifully, and which harmonizes with the detailed set design to eye-popping results. Production designers Shona Heath and James Price synthesize a wide range of art styles to create the film’s rich milieu: the swirling facades and canted doorways, especially when distorted through cinematographer Robbie Ryan’s ubiquitous fish-eye lenses, recall the films of the German expressionist movement and 1930s Hollywood monster movies. Still, for all the elements of Frankenstein or Dr. Caligari, there is equal measure of The Wizard of Oz, for the film’s sprawling tableaus and Boschian painted backdrops invoke the grandiose artifice of Hollywood’s Golden Age (thus, it was understandable that Price and Heath resisted describing the film as “steampunk” when asked to comment, rightly insisting on the film’s aesthetic elasticity in spite of such superficial labels).

With Poor Things, Lanthimos reaches new heights in a year full of big swings from established auteurs. Undoubtedly in conversation with Greta Gerwig’s IP-trojan horse sensation Barbie, Poor Things brings an absurdist edge to the recent streak of irreverent, feminist-inflected films—and has the potential to overcome its glossy pink counterpart’s long-term cultural cachet. Come the film’s wide release, I would be unsurprised to see Lanthimos become more of a household name, if not bring home the bacon this awards season (that is, if incumbent Academy members aren’t too scandalized). To some degree, Poor Things is a departure from Lanthimos’ trademarks, but it is also his most towering work to date.